The field of energy harvesting focuses on the collection of ambient energy from the local environment that would otherwise be wasted. This ambient energy is predominantly found in three forms: kinetic energy from relative motion and vibrations, electromagnetic waves including radio waves, and heat dissipated from machines and electronics. Around 70% of the world’s generated electricity ultimately ends up as waste heat after its use [1], [2]. Such waste is an unavoidable consequence of the laws of thermodynamics. An efficiency of 100% can never be achieved and energy always tends to be converted to a less ordered state – the least ordered form being heat. With each conversion, the entropy of a closed system will always increase. Electrical systems dissipate thermal energy due to the resistances of their components while in mechanical systems, heating due to friction can never be completely eliminated. For example, petrol and diesel engines are only about 30% efficient at best as a result of friction as well as lost heat from combustion. Recovering part of this dissipated heat means we can make more efficient use of our finite energy resources [1].

Solid state devices called Thermoelectric Generators (TEGs) can produce electricity from the temperature difference between the two ends of one or more thermocouples. A thermocouple is simply made up of two chemically dissimilar materials joined together by a conductor. Heating or cooling the ends of these materials creates an electric current [1]. This phenomenon is known as the Seebeck effect and was discovered in 1826 by German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck [2]. He experimented with a thermocouple that used two different metals and found that a magnetic field is produced when the end junctions of the thermocouple are exposed to different temperatures. The magnetic field was later found to be created by the electric current through the metals. Shortly after it was discovered that metals only exhibit a very weak Seebeck effect, making them inefficient at converting heat to electricity. A breakthrough came in 1929, when Russian physicist Abraham Ioffe observed that semiconductors exhibit a much stronger Seebeck effect. They were found to be up to 40 times more efficient than metals as thermoelectric materials [2].

Usually, thermoelectric materials are made into ‘legs’ that can stand upright such that the sides joined together are kept at a high temperature while the exposed ends are kept at a low temperature. This arrangement of a thermocouple is illustrated in figure 1. The electrons or electron holes in metals and semiconductors are able to move much like gas particles. If a temperature gradient forms within a material, the charge carriers at the hot end will tend to diffuse to the colder end, producing a net charge. The heat flow is also carried by vibrations in the metallic lattice. These vibrations of groups of atoms are known as phonons [3]. In the thermoelectric materials, energy provided from the temperature gradient overcomes the electrostatic repulsion amongst charge carriers at the cold end, therefore a voltage across the two dissimilar materials is produced.

Within modern semiconductor-based thermocouples, one leg is made out of an n-type semiconductor while the other is made out of a p-type semiconductor. When the top side of the thermocouple is heated, electrons in the n-type leg accumulate at the bottom, cold side, while in the p-type material, electron holes (with a ‘virtual’ positive charge) diffuse to the cold side [3], [4]. Therefore, an electromotive force – which also gives rise to a current – is produced across the cold ends of the n-type and p-type materials. Most commonly, a Bismuth-Tellurium-Antimony (Bi2Te3–Sb2Te3) alloy is used for the p-type leg and a Bismuth-Tellurium-Antimony-Selenium (Bi2Te3–Sb2Se3) alloy makes up the n-type leg [1]. In practical thermoelectric generators, many thermocouples are connected together in series to maximise the output voltage [4]. As far as heat flow is concerned, the thermocouples in TEGs are connected in parallel as they share the same heat source and the same heat sink.

The voltage across a thermoelectric material (V) depends on the temperature difference () between its top and bottom sides and can be written as

, where S is known as the Seebeck coefficient [1], [3]. There is a non-linear relationship between V and

, so S is temperature dependent.

For a device such as the one shown in figure 1, the voltage across it is simply the difference between the potentials at the two legs, . The Seebeck coefficient of the device itself is given by

.

A thermocouple’s output power (and by extension the power of a TEG) is limited by its series resistance as well as by the power conversion efficiency, which is defined as the electrical output power, W, divided by the total heat flow, Q. As a result, the performance of TEGs can be optimised by selecting materials with a high Seebeck coefficient, low thermal conductivity (to minimise Q) and high electrical conductivity (to maximise carrier charge diffusion) [3]. From a materials science perspective, this means it is desirable to use materials that conduct heat mostly through free electrons or electron holes rather than through phonons. In an effort to identify new suitable thermoelectric materials, a team of researchers led by Jan-Hendrik Pöhls at McMaster University [2] is using quantum computations to model various materials and predict their properties. They have identified more than 500 materials with the desirable properties discussed previously that could greatly improve the efficiency of thermocouples.

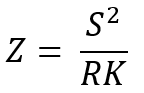

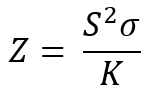

A figure of merit for thermoelectric generators, often denoted by Z in scientific literature, is given by:

Where: R is the thermocouple’s series resistance and K is the thermal conductivity in . Since the resistance is just the inverse of the conductivity (

), the above formula is equivalent to:

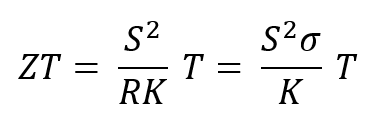

Another quantity used to measure performance is the Z-value multiplied by the average temperature. This quantity (ZT) is dimensionless and temperature dependent [3].

In the above formula, the numerator, , is called the power factor – it is a measure of the power obtained per unit length for a 1° difference in temperature. The heat conversion efficiency increases with the ZT value and for most practical purposes, ZT needs to be greater than 1. So far most thermoelectric generators have quite low efficiencies of around 4-5%, however research into new thermoelectric materials could see this figure rise to 10% [4]. Despite relatively low efficiencies, TEGs are solid-state devices with no moving parts and they can be placed in small, inaccessible spaces or hostile environments.

Interestingly, the Seebeck effect is actually thermodynamically reversible. In other words, instead of powering a thermocouple with a temperature gradient (hot to cold) to produce electricity, it can be powered with electricity to produce an inverse temperature gradient (cold to hot). A voltage applied across the thermocouple legs will produce cooling at the side that was previously kept hot. This is known as the Peltier effect and is used in small, portable refrigerators and dehumidifiers [2].

Powering Wireless Sensor Networks

One important application of energy harvesting is to power miniature sensors, linked together in wireless networks. Wireless sensor networks (WSN) are an essential building block of the Internet of Things (IoT) – a concept in which sensors are embedded into physical objects or devices, ranging from home appliances to industrial machinery, for the purpose of exchanging collected data with other systems over the Internet [5], [6], [7]. It has been projected that the number of IoT connected devices will increase to over 75 billion by 2025 [7]. Although energy harvesting technologies require small batteries or capacitors to temporarily store collected energy, using batteries as the only power source is simply impractical for such large numbers of remote sensors due to the need for recharging or replacements. The additional weight and bulk of batteries are also disadvantages in certain industries such as robotics or aerospace, therefore energy harvesting is likely to become increasingly important.

A wide range of environmental variables such as temperature, pressure, humidity and light intensity can be monitored by WSNs. Typically, a huge amount of data is collected and then transmitted over the Internet to cloud-based computers which process it to extract trends and information that is meaningful to users. Sensors are crucial in many industrial and scientific applications as they can remotely monitor complex systems and identify potential problems before they arise [5].

Newer generations of sensors that meet IoT standards are more sophisticated than ones that simply convert physical variables into analogue electrical signals. They have to meet a specific list of requirements. In addition to basic requirements like low cost, wireless communication and unobtrusiveness, IoT sensors must be capable of self-diagnostics and data pre-processing (processing collected data on the spot to reduce the workload of cloud computers) [5]. The list of features and applications goes on. As the energy demands of microelectronics and sensors continue to fall, energy harvesting is looking increasingly more realistic for widespread use [8].

Applications in Space Exploration

Since its inception, the space industry has relied on TEGs combined with thermal generators based on nuclear technology. These generators are known as Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) and they do not use conventional nuclear fission technology. Instead, they harness the heat from the natural radioactive decay of Plutonium-238 (which is stored as Plutonium dioxide). Space missions cannot always rely on solar power, whose intensity rapidly decreases with increasing distance from the Sun. There are also often strict limits on the size and weight of the probes to be launched. In these cases, the advantages of RTGs become apparent. The technology was first used on the US Navy’s Transit navigational satellite in 1961. Its RTG generated only about 2.7 W but worked for over 15 years [9]. Due to their compact size and high reliability, RTGs also powered the famous Voyager I and Voyager II space probes. They were each equipped with 3 RTGs supplying 423 W of power from about 7000 W of thermal power. The Voyagers’ power supply gradually decreased by around 7 W per year but remarkably some instruments on both spacecraft are still functioning after more than 40 years [9], [10].

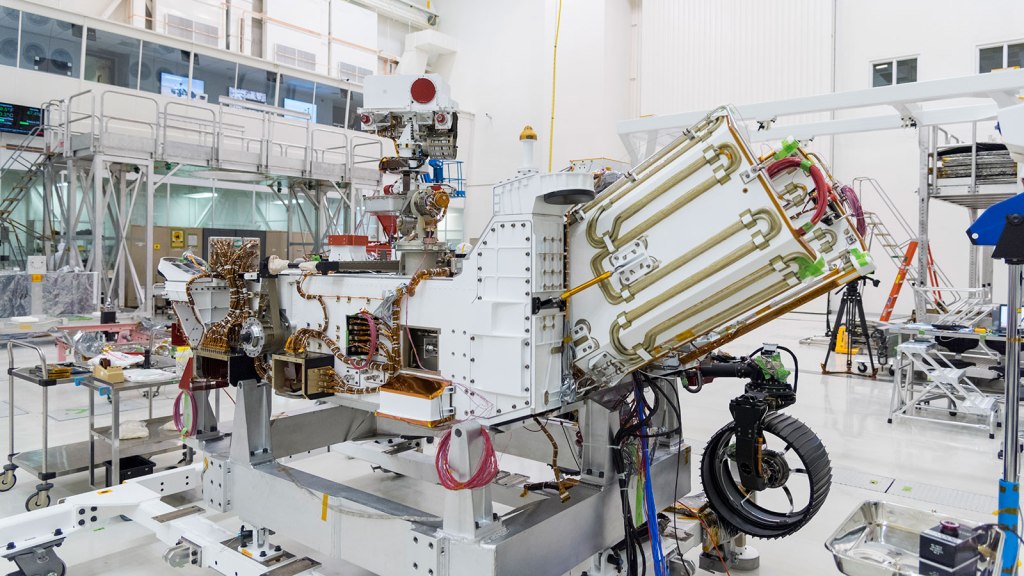

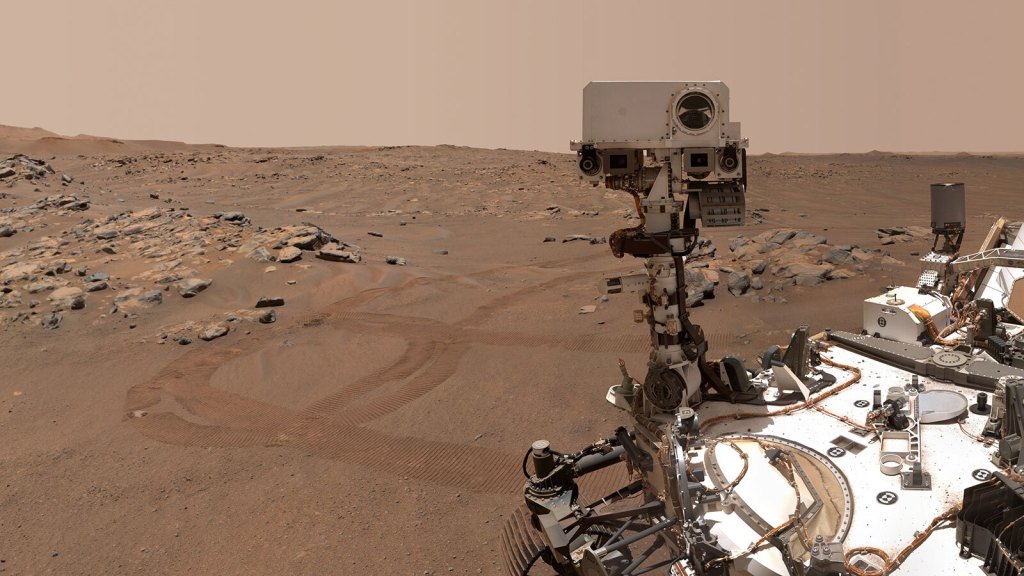

Source: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/fueling-of-nasas-mars-2020-rover-power-system-begins

Another famous example of a space probe powered using TEGs is the Cassini-Huygens probe launched by ESA and NASA in 1997 [9]. It has conducted extensive studies of Saturn as well as transmitting some breath-taking images. More recently, thermoelectric generators proved vital in the missions of the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, launched in 2012 and 2021 respectively. Their RTGs provide around 110 W of power each [11]. The image in figure 2 above shows the section of the rover dedicated to the RTG power plant. Although solar panels have been used on previous Mars missions (such as the Spirit and Opportunity rovers), they would struggle to provide enough power to larger and more sophisticated rovers like Perseverance and, of course, there would be no power at night.

Source: https://mars.nasa.gov/news/9060/roving-with-perseverance-nasa-mars-rover-and-helicopter-models-on-tour/

Waste Heat Recovery in Industry

Nearly all industrial processes produce heat as a by-product. In some cases, waste heat can be reused by heat exchange pipes for domestic heating networks or even converted into electricity using Sterling engines. Most of the time, waste heat is released into the atmosphere. An example of heat recovery in the steelmaking industry is a 10 kW TEG system implemented by JFE Steel Corporation in Japan. This system uses radiant heat from casting slabs to power a 4-by-2 metre arrangement of TEGs that are connected to the grid. At a slab temperature of about 900°C, the system is able to produce 9 kW [9].

Domestic TEGs in Developing Countries

It is estimated that in developing countries, 17% of the population does not have a secure connection to the electricity grid [9]. In more economically deprived regions, biomass is the main source of energy. Wood burned in stoves or fireplaces is not only inefficient but it also produces harmful fumes and particulates in many homes. For example, data from the WHO suggests that some homes in India have a particulate concentration of over 2000 µg/m3 while the safe limit in the United States is considered to be 150 µg/m3. This has been found to cause 400,000 premature deaths per year in India [9]. Making wood-burning stoves more efficient and less polluting can help mitigate against these problems. A possible solution is to use fume extractors powered by thermoelectric generators, which are in turn heated by the fire. These fume extractors help achieve a more complete combustion (by oxygenating the fire) while at the same time removing smoke and particulates. Furthermore, excess electricity can be stored in batteries or used to charge mobile phones, power lights and radio sets – basic comforts that can make a huge difference to the lives of many people. Thermal energy harvesting can also play a role in concentrated thermal solar energy systems. Vacuum tube panels for heating water can be equipped with TEGs in cogeneration schemes that provide both hot water and electricity.

Conclusions

This article first looked at the basic physics behind how thermoelectric generators work and then explored some of the main areas for application which also have a potential for growth in the future. It is clear that TEGs have the potential to contribute to increasing the energy efficiency of many systems – ranging from large scale industrial processes to low power devices such as wireless sensors. Despite their relatively low efficiencies, TEGs offer the advantages of low-cost materials for manufacturing as well as high reliability due to the lack of moving parts and the lack of complex electronics. This technology is especially important in space exploration as it is one of the few reliable options for supplying power in the harsh conditions in outer space. There are also limitations on the mass of the payloads that can be launched by rockets, therefore other options such as batteries are not always practical. A detailed review of other interesting uses cases for TEGs is given in the paper by Champier [9]. The author further comments on how this technology can enable cogeneration with solar thermal panels – providing both hot water and electricity. Future research into finding new more efficient thermoelectric materials, such as the quantum computing modelling done by Pöhls et al. [2] will hopefully lead to some exciting developments for the field of energy harvesting.

References

[1] H. Akinaga, “Recent advances and future prospects in energy harvesting technologies”, Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, vol. 59, no. 11, 2020. Available: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.35848/1347-4065/abbfa0#jjapabbfa0s4. [Accessed 12 January 2022].

[2] J. Pöhls, “A new approach finds materials that can turn waste heat into electricity”, The Conversation, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://theconversation.com/a-new-approach-finds-materials-that-can-turn-waste-heat-into-electricity-173472. [Accessed: 05- Jan- 2022].

[3] M. KIZIROGLOU and E. YEATMAN, Materials and techniques for energy harvesting. Imperial College London.

[4] D. Enescu, “Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting: Basic Principles and Applications”, Green Energy Advances, 2019. Available: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/65239. [Accessed 4 January 2022].

[5] “Smart Sensor Technology for the IoT”, Techbriefs.com, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.techbriefs.com/component/content/article/tb/pub/features/articles/33212. [Accessed: 11- Jan- 2022].

[6] M. Di Paolo Emilio, “Design Fundamentals of Energy Harvesting for Industry”, Power Electronics News, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.powerelectronicsnews.com/design-fundamentals-of-energy-harvesting-for-industry/. [Accessed: 05- Feb- 2022].

[7] “What is energy harvesting?”, Onio.com, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.onio.com/article/what-is-energy-harvesting.html. [Accessed: 09- Jan- 2022].

[8] “Energy harvesting applications | Faculty of Engineering | Imperial College London”, Imperial.ac.uk, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/electrical-engineering/research/optical-and-semiconductor-devices/research/energy-harvesting-applications/. [Accessed: 06- Jan- 2022].

[9] D. Champier, “Thermoelectric generators: A review of applications”, Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 140, pp. 167-181, 2017. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196890417301851. [Accessed 8 January 2022].

[10] “Voyager – Mission Overview”, nasa.gov. [Online]. Available: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/. [Accessed: 20- Jan- 2022].

[11] “Perseverance Rover – Electrical Power”, mars.nasa.gov. [Online]. Available: https://mars.nasa.gov/mars2020/spacecraft/rover/electrical-power/. [Accessed: 21- Jan- 2022].