Finding ways of generating reliable and sustainable energy will be a top priority for civilization in order to maintain our standard of living and economic development. The growth of developing nations will place an ever increasing demand for energy since generally, the annual energy use per capita is correlated with a country’s GDP per capita. For example, the BRICS nations follow this trend, with India and Brazil’s consumption growing by 50% and 38% respectively in the past 20 years [1].

A great deal of money and effort has been put in the development of renewable energy in the past decade, rightly so. However, solar (photovoltaic and thermal), wind, biomass, geothermal and hydroelectric still account for a small fraction of current production. As a whole, renewable sources contributed 4.14% of all global energy production in 2018. In 2010, solar and wind produced 0.25% of global energy, growing to 1.15% in 2018. Hydroelectricity, another important source, grew by only 0.3% in the decade 2008-2018 as shown in [1]. In comparison, nuclear energy currently provides more than 10% of the world’s electricity demand and 18% of electricity in developed OECD countries.

Most renewables rely quite heavily on government subsidies and use large land areas which are often needed for other purposes including growing crops. This often leads to scarcity of suitable land which means higher costs. Another issue is that renewables are intermittent, so energy storage is crucial here, but infrastructure such as domestic battery packs is not yet widespread. At least for the near future, there is a need for a reliable source for the base load – this is where nuclear energy may be most valuable [2]. Solar power also has massive potential for expansion with both photoelectric and thermal plants, provided that energy storage schemes are built on a large scale for continuous supply. The aim of this article is to outline several nuclear technologies that offer a realistic solution for powering the planet.

Energy from Fusion

“I would like nuclear fusion to become a practical power source. It would provide an inexhaustible supply of energy, without pollution or global warming.”

Stephen Hawking

Nuclear fusion is arguably the most promising and potent energy source currently being developed. It will eventually provide highly efficient, clean energy by harnessing the same process that powers the stars. Moreover, fusion has none of the meltdown risks associated with conventional fission reactors that many people are apprehensive about. Fusion devices have been around for over 60 years but the real challenge is to achieve a controlled reaction capable of producing a net energy gain. So far no reactor has even come close to breakeven in terms of energy balance.

Background

In a fusion reaction, nuclei with a low atomic number combine to form a heavier nucleus and release large amounts of energy. To do this, extreme temperatures on the order of K are necessary for enough kinetic energy to overcome the Coulomb force – a strong electrostatic repulsion between the protons in the nuclei to be fused. Once two or more nuclei are close enough together, the strong nuclear force takes over to join them. At these sufficiently high temperatures, the process becomes self-sustaining. Hydrogen, with its isotopes deuterium and tritium most readily take part in these reactions as they have the smallest positive nuclear charge of +1, hence the smallest Coulomb barrier [3], [4], [5]. Reactions with heavier elements occur in every star but they are far more difficult to achieve artificially. In fact, large stars can synthesise elements up to Iron, after which, heavier elements are made in supernova explosions that also spread them out into interstellar space.

It has been experimentally discovered that Deuterium-Tritium fusion reactions are the most efficient for power generation because they have the highest energy gain for comparatively low temperatures. In other words, the energy released divided by the temperature needed is at a maximum.

Reasons for pursuing fusion power

- Fusion reactions are millions of times more energetic than combustion of fossil fuels as there is a direct conversion of matter to energy. The reaction products combined (Helium and a neutron) have slightly less mass than the starting nuclei, with the difference in mass turned into energy according to

.

- For equal fuel masses, fusion is also four times as energetic as fission reactions. In other words, Deuterium and Tritium have a huge energy density.

- It is also a sustainable process because Deuterium can be easily obtained from seawater while Tritium can be produced when fast fusion neutrons react with Lithium (a relatively abundant metal on Earth). Tritium is thus regenerated by the reaction itself.

- No toxic pollutants, no greenhouse gases and no dangerous radioactive isotopes are released. The main waste product is Helium – a valuable gas in industry that the world is actually running out of.

- There is no risk of meltdown as fusion requires very precise conditions. Any damage to equipment will cool the plasma, causing the reaction to stop. At any given time the amount of fuel in the reactor is enough for only a few seconds of ‘burning’, therefore there is no chance of a chain reaction [6].

ITER Fusion Reactor

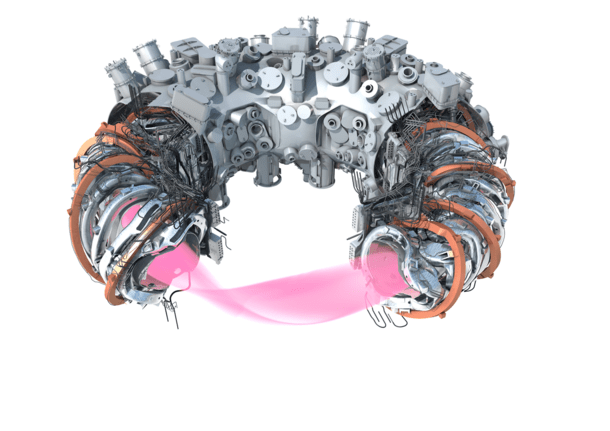

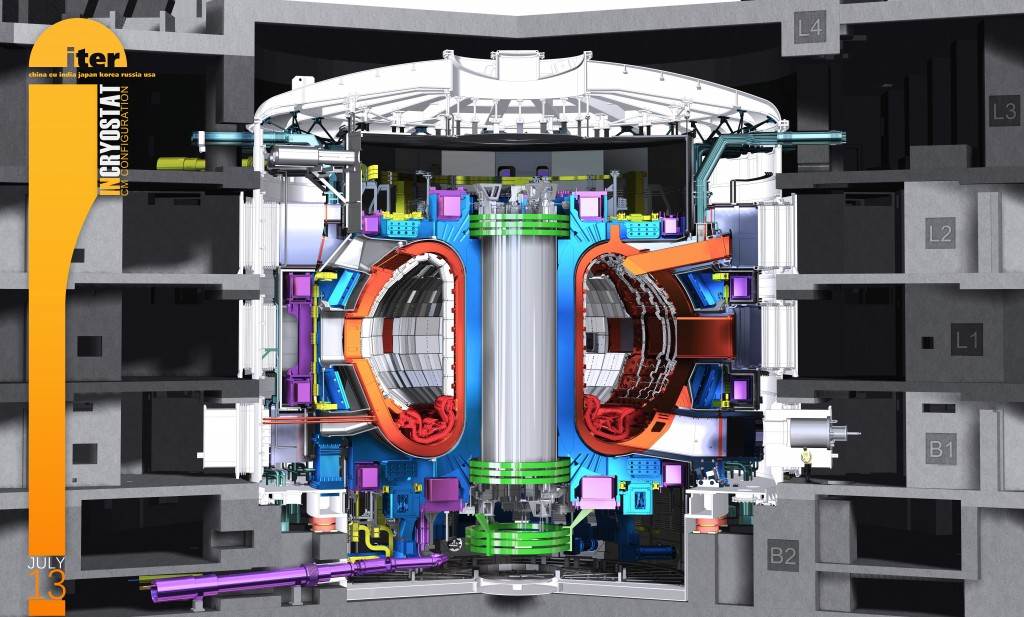

ITER is currently the largest experimental nuclear fusion project in the world under construction at the Cadarache research facility in southern France. It is a collaboration of the European Union, China, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea, the UK and the United States. The reactor design is a so called ‘tokamak’ device, which is a vacuum chamber shaped like a toroid (or a doughnut) and uses strong magnetic fields to confine super-heated plasma that reaches 150 million degrees Celsius – ten times hotter than Sun’s core (the Sun has the additional advantage of huge pressures) [6].

A mix of Deuterium and Tritium will be heated to a plasma at extreme temperatures and kept in this state in a carefully controlled way to start the fusion reaction. Heating is done by two sources of high frequency radio waves and an injection of high speed uncharged fuel atoms. A device called an ion cyclotron creates an EM beam with a frequency of 40 to 55 MHz, while at the same time an electron cyclotron produces an even more intense beam at 170 GHz, the resonant frequency of electrons. The fusion reaction releases its energy through many high speed neutrons as well as electromagnetic radiation. Cooling systems circulate water throughout the tokamak to absorb the energy produced and send it off to a cooling tower [7].

The goal of ITER is to show that it is possible to generate more energy from the fusion reaction than is used to initiate it – a net energy output. However, it is still a research project which won’t be generating usable power for the grid since no turbines or generators will be built [6]. ITER will serve as a prototype reactor and information gathered from tests there will be invaluable for refining future power plant designs.

Researchers use a value called the fusion energy gain factor (Q), defined as the ratio of the output power to the power required to maintain the reaction, so if Q < 1, a reactor consumes more power than it produces. So far every experimental fusion reactor is in this category. If Q = 1, consumption and production are equal, also known as the breakeven point. As you may have guessed, the ultimate goal is to reach a value of Q > 1, but also a value high enough to compensate for the losses inherent in transferring the heat to boil water and running a turbine with a generator. The current record for the highest Q factor is 0.67, achieved by the Joint European Torus (JET) in the UK (Figure 2), which used 24 MW to produce 16 MW. The plan is that ITER will be able to generate 500 MW using only 50 MW, a ten-fold increase or Q = 10. Its larger toroidal volume of 840 m3 means more plasma can be contained compared to older reactors [6], [7]. Therefore, many more nuclei can be fuse per unit of time, releasing significantly more energy. Of course, this is a bit of an optimisation problem or a balancing act because too large a volume can also require more heating energy.

It is hoped that a state of ‘burning plasma’ is achieved, whereby the produced Helium nuclei have enough kinetic energy to maintain a high temperature. At the same time, the heat in the torus is contained very efficiently, meaning that there is little energy loss and the reaction continues for longer. The external heating can then be reduced or switched off for a certain time. A plasma dischrage pulse refers to a period in time when the plasma is left to release its fusion energy without external heating. The aim is to have a minimum pulse of 500 seconds with burning plasma that can produce at least 50% of the energy needed to sustain the reaction internally [6], [7].

The planning for next step after ITER has already begun with the DEMO reactor. It will be 15% larger than ITER with a fusion gain factor of 25 and unlike its predecessor, it will generate electricity using steam driven turbines and generators. DEMO’s expected power output of 2000 MW will be comparable to that of today’s large conventional power plants as discussed in [10]. If all goes to plan, it will be operational by 2033 and will lead the way for rapid commercialization of this technology.

Figure 2 – Interior of the Joint European Torus (JET). Source: www.euro-fusion.org

Energetics of fusion

The reason for the huge amounts of energy produced in these nuclear reactions can be understood through the matter-energy equivalence, famously stated by Einstein’s equation . Matter and energy are interchangeable, with the speed of light squared acting as a constant of proportionality or an ‘exchange rate’ between the two. As

is a huge number, a tiny amount of mass can store a significant amount of energy. In the reaction of Deuterium with Tritium, the total mass of the products (Helium and a neutron) is slightly less than the combined mass of the reactants. The difference in mass, often called a mass defect, is released as energy [8], [9].

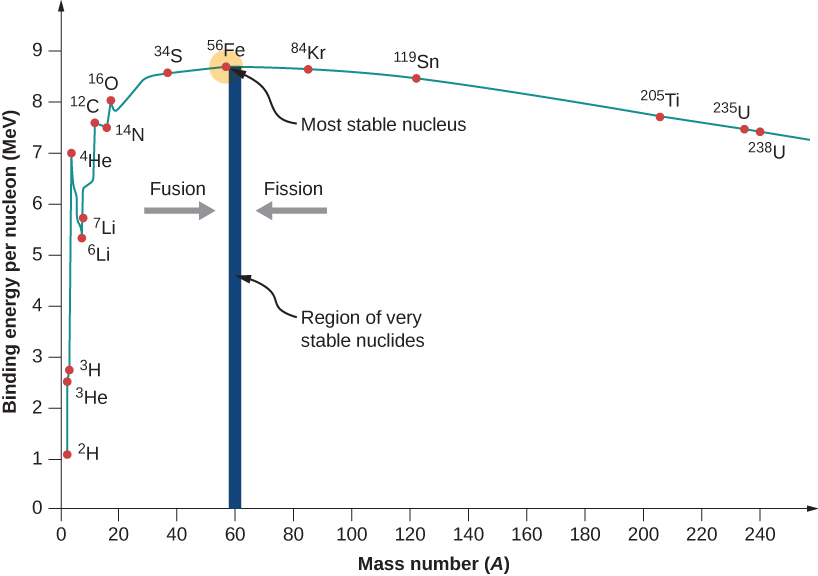

To understand this further, we need to look at the concept of binding energy per nucleon. If a nucleus is broken up into its constituent protons and neutrons, the total mass of these individual nucleons will be greater than the mass of the nucleus itself. When protons and neutrons combine (fuse), this small difference in mass is converted to energy according to

, with the energy divided by the number of nucleons equalling the binding energy per nucleon. ‘Binding’ refers to the fact that this is how much work needs to be done to get the nucleons outside of the influence of the binding strong force. The greater the difference in binding energies between reactants and products, the more energy is produced. Figure 2 shows a graph of binding energy per nucleon versus number of nucleons (protons and neutrons). The graph has a peak at Iron, which is the most strongly bound and therefore the most stable nucleus. Fusion of light nuclei results in a climb along the graph to the right, to higher product binding energies. It is this steep slope that helps explain why fusion is such a highly energetic process [8], [9]. Conversely, fission of heavy nuclei is a movement from right to left on the graph, but since the slope to the right is much smaller, far less energy is released.

Image credit: Steven Mellema, The Cosmic Universe. OpenStax CNX, https://cnx.org/contents/lQXiC0Me@73.1:FRY7QqvG@3/Nuclear-Binding-Energy

Although the SI unit for energy is the Joule, when showing single reactions in nuclear physics, another unit called the electron-volt (eV) is preferred as energy changes tend to be small (1 eV = J and 1 MeV =

J). Some examples of reactions with their energy yield are shown below.

For the Deuterium-Tritium reaction (middle equation), about 80% of the yield, or 14.1 MeV, is released through the neutron in the form of kinetic energy [8].

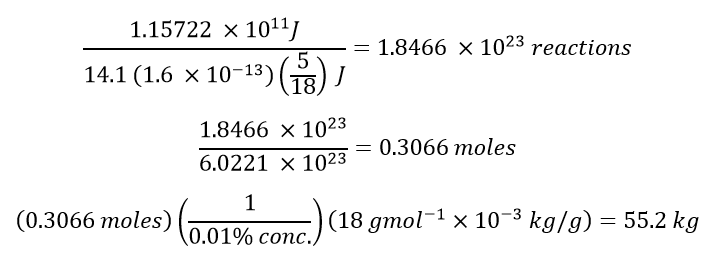

In the UK, an average person consumes about 32,145 kWh per year, which equals Joules [1].

To provide this, we need reactions or 0.0852 moles of Deuterium. Its abundance in water is about 0.01%, which suggests that 855.16 moles or 15.4 litres of water are required.

There’s a problem though, as this calculation neglects that power plants only convert about 1/3 of their heat to electricity due to losses during energy transfers [2]. The gain factor Q also has to be taken into account and here it is assumed to be Q = 5 (half that of ITER). Putting these together means we need to multiply the energy released in each reaction by a loss factor equal to (1/3) (5/6) = 5/18. Avogadro’s constant is used to work out the number of moles that take part in reactions, which in turn allows us to get a figure for the mass of water.

Only 55.2 litres of water is needed per person for an entire year’s worth of Deuterium. An equal number of moles of Tritium have to also be formed by bombarding Lithium with neutrons. This is roughly the volume of a car petrol tank, so the availability of fusion fuel will not be a problem at all.

Other isotopes such as Helium-3 have been suggested as fuels to use alongside Deuterium. Reactions with Helium-3 release a lot of their energy through high speed protons, which can be contained with magnetic fields, removing the need for heavy neutron shielding. These protons could also directly produce electricity with high efficiency when interacting with a magnetic field. Despite this, Helium-3 has been side-lined in favour of Deuterium and Tritium because of its high Coulomb barrier and scarcity on Earth (although there are large deposits on the Moon). In addition, we will see that a lack of neutron release would make certain reactor technologies impossible. At the very least, Helium-3 offers another development route should we ever need it. If humanity establishes lunar colonies, they could make use of the Helium-3 on the Moon for power.

Technical Challenges

We must also be aware that the development of fusion has been very complex and difficult. There is a saying that controlled fusion is always ‘only 30 years away’ which has been stated since the 70s. Stars make it look easy, but on Earth, the tokamak’s magnetic field has to be extremely fine-tuned to ensure the plasma is compressed evenly without irregularities or bulging. Gravitational fields are only attractive, so stars can achieve even compression without difficulty, but electric and magnetic fields form dipoles. It takes supercomputers to plot the precise magnetic and electric fields in a volume of charged particles such as the plasma in a toroid [10].

Another problem facing tokamaks is disruptions when plasma energy is released in an uncontrolled way. This is usually a result of the superconducting magnets not maintaining the required field strength. Nevertheless, progress is being made in this area, with the Japanese JT-60 achieving 30 seconds of disruption free pulses at a time [2]. If all goes well, ITER will be pushed to 500 second pulses of plasma burning while DEMO will be designed for continuous operation.

Inside a tokamak, a current of plasma around the centre of the toroid produces a magnetic field that wraps around the ring vertically, known as a poloidal field. At the moment, there are problems with driving the plasma current steadily, which is important for proper confinement. Without a stable poloidal field, the plasma shape becomes irregular. A transformer coil is used to produce this current, although there is also research into using microwave pulses for the same effect.

Wendelstein-7X stellarator reactor

A ‘stellarator’ is a different reactor design that does not use a plasma current and so avoids the instability issues that come with it. As with a tokamak, it uses magnetic confinement, but has a more complex twisted ring shape with modular superconducting coils as can be seen in [11] or Figure 6. Typically the magnetic field is designed to be close to a flat two dimensional field. The internal shape of the stellarator is determined using mathematical models to reduce charged particle drift, meaning that a current is not required for strong confinement forces. A charged particle travelling on the outside wall in one of the curved sections will move to the inside in the next section and as a result, an upward drift on one side is cancelled out by a downwards drift on the other.

One of the largest stellarators is the Wendelstein 7-X in Germany, run by the Max Planck Institute. It has demonstrated continuous steady operation with plasma discharges lasting 30 minutes, so disruptions are far less common with this design compared to tokamaks. Construction finished in 2014 and it achieved first plasma ignition on the 10th December 2015.

Figure 4 – Wendelstein-7X reactor assembly (Source: http://www.theverge.com, Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Figure 5 – Plasma within the stellarator chamber (Source: http://www.fusenet.eu)

Figure 6 – 3D computer model (Source: Max Plank IPP)

What is breeder reactor?

Given appropriate conditions, the neutrons released in nuclear fission reactions of heavy elements can interact with non-fissionable isotopes to produce more fuel for a reactor. This process is known as ‘breeding’. As a result, a breeder reactor is able to generate more fissionable material than is used as fuel. Alongside its starting fuel of Uranium-235, it contains so called fertile materials that become fissionable isotopes or new elements after absorbing neutrons. The most common breeding reaction is the conversion of Uranium-238 into Plutonium-239 [12].

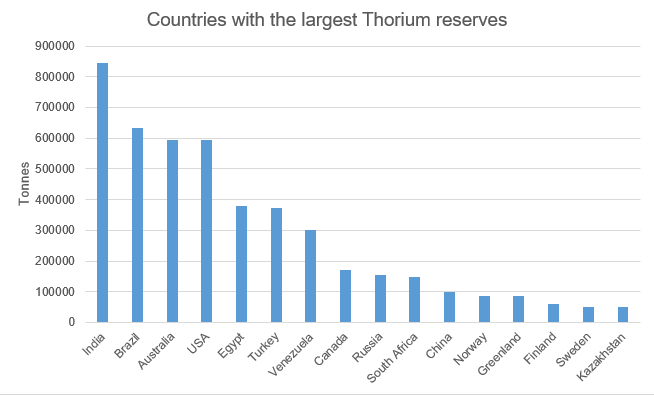

Regular fission reactors are limited primarily to Uranium-235 for fuel, which makes up only 0.7% of all naturally occurring Uranium ores, with the rest being mostly Uranium-238. Enrichment is sometimes needed to increase this concentration to about 3-5%. In contrast, breeders can use approximately 70% of their Uranium-238 for producing power. Furthermore, Thorium-232 is another common fertile material that is able to breed Uranium-233. Significantly more ore deposits are available for fuelling breeder reactors given that Uranium-238 is 140 times more abundant than Uranium-235 and that there are sizeable reserves of Thorium (Figure 8). This clearly has economic benefits that can make nuclear electricity more affordable for consumers and industry.

A major advantage over regular reactors is that breeders can make more complete use of their fuel. In addition, they can eliminate the most hazardous components of nuclear waste. The products of nuclear fission consist of many isotopes lighter than Uranium. Spent nuclear fuel also includes atoms heavier than Uranium that are part of the actinide series (at the bottom of the periodic table). These trans-uranic actinides are the most dangerous waste because of their very long half-lives which result in thousands of years of radioactivity. Breeder reactors are designed to extract energy from actinide waste, converting them to smaller, much less dangerous nuclei with relatively short half-lives. The nuclear industry already has expertise on safely dealing with such waste. The two main configurations are compared in Table 1 below.

| Fast Breeder Reactor | Thermal Breeder Reactor | |

| Fuel | Uranium-238 | Thorium-232 |

| Neutrons released | Fast, high energy neutrons | Slower, thermal neutrons |

| Moderation | No | Yes |

A promising type of fast breeder reactors is the Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactor (LMFBR) in which molten liquid Sodium acts as a coolant for heat transfer. No moderators are used as high energy neutrons are more efficient at transmuting Uranium into Plutonium. Water would act as such a moderator and therefore it cannot be used. Liquid Sodium has a very high heat capacity and does not need to be pressurised like water to remain a liquid at high temperatures. As a result, bursting of pipes is far less likely, however if any bursts occur they are potentially much more dangerous as Sodium is highly reactive.

Thorium as an alternative fuel source

Thorium has a unique ability to breed fission fuel using slower thermal neutrons. Compared to fast breeders, more neutrons are sent off for each absorbed neutron and therefore more spent fuel can be reprocessed, which theoretically doubles available fuel resources. In addition, Thorium thermal breeders are far less complex in design than fast breeders since light water is the only coolant. Water moderated systems are well known, tried and tested technology [12], [13].

A Thorium-Uranium fuel cycle does not involve reactions with Uranium-238 and therefore no dangerous transuranic elements are produced. This also removes the risk of weapons proliferation from Plutonium. Moreover, Thorium is about 3 times more abundant than Uranium in the Earth’s crust, at a concentration of 0.0006% compared to 0.000018% for Uranium. Despite this not all Thorium deposits are economical to extract in addition to the fact that sea water also contains small amounts of Uranium, meaning that the two fuels are roughly equally abundant [12], [13].

One innovative concept that is suitable for the Thorium fuel cycle is a Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) known as the Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor (LFTR). Instead of pellets placed in rods, fuel is dissolved in a molten fluoride (or chloride) salt, which is directly heated by the fission chain reactions. The salt forms a convection current through a heat exchanger to transfer heat to a steam turbine. A distinctive feature of a MSR is that chemical processing to remove spent fuel and refuelling can be done without shutting down the reactor. Smaller waste nuclei can be quickly removed from the core, preventing them from absorbing neutrons that would otherwise continue the chain reaction. Fewer lost neutrons means more fuel efficiency [14]. As an example of the potential sustainability of breeders, a Thorium fuelled light water breeder reactor in Shippingport, Pennsylvania had 1.4% more fissile fuel at the end of its 5 year operation that it started with [13], [15].

Fusion-Fission hybrid reactors

Hybrid nuclear reactors are a proposed method of combining fusion and fission reactions to generate energy. This technique relies on the fact that high energy neutrons from a fusion reaction can breed nuclear fuel for a separate fission reactor. It was first proposed by physicists Andrei Sakharov and Hans Bethe in the 70s but has not been explored recently. Fertile materials to be processed can be placed in a ‘blanket’ surrounding the central fusion reactor. These reactors are in theory much easier to design for power generation because the power and materials requirements for the fusion core are not as stringent compared to pure fusion – a relatively low Q-gain factor is needed. Fusion breeders could be very useful in the transition to pure fusion power. They offer the advantage of complete depletion of their nuclear fuel whilst also releasing more energy than fission breeders [2], [16].

With pure fusion, a fast neutron with a kinetic energy of 14.1 MeV transfers energy to boil water in a heat exchanger. In a fusion breeder, this also happens, but additionally the neutron reacts with a fertile material to form fuel that can provide energy by fission. Once again, as with the fission breeder, Thorium-232 can be converted to Uranium-233 which then splits to release 100-150 MeV. In effect, this multiplies the energy output of the first reaction [2]. Thorium could not fuel a regular fission reactor, but a hybrid can make it usable. This type of hybrid reactor breeding requires elements that act as neutron multipliers such as Beryllium, Lead or Uranium that give out multiple neutrons when interacting with a single high energy fusion neutron. Part of the neutrons have the job of reacting with Lithium to re-form tritium [2].

In both fission and fusion (with neutron multipliers in fusion), each reaction emits either 2 or 3 neutrons. In fission, one neutron has to continue the chain reaction whereas in fusion one is needed to breed Tritium from Lithium, so in either case an average of 1.5 neutrons remain available to use for other purposes. In reality there are always some losses, which leaves ~0.75 neutrons to breed Plutonium-239 from Uranium-238 or Uranium-233 from Thorium-232. Of course there cannot be fractional neutrons, so this comes from the fact that not every reaction will have a leftover neutron [2], [16].

A single Deuterium-Tritium reaction involves a smaller mass to energy conversion than fission (as they have a tiny mass to begin with), which is why it releases about 18 MeV, compared to 200 MeV for the splitting of a more massive Uranium nucleus. This suggests that for reactors of equal power, approximately 11 times more neutrons are released by fusion, which we can think about as a high neutron-to-energy ratio. Conversely, fission offers a low ‘neutron-to-energy’ ratio, so the two complement each other nicely. This is the reason why fusion breeding has an advantage over its fission counterpart – roughly eleven times more fertile nuclei can be transformed into useful fuel [2], [16]. Hybrids do not necessarily have to breed more fissile materials. A fission blanket can simply be used as an energy multiplier for a fusion core. A valuable safety feature of this set up is that stopping the fusion reaction also stops the fission [16].

There is debate around what would be the most practical hybrid design, with two options. One design concept is to have the fission and fusion reactors close together in order to make it easier to use the newly produced fission fuel. There would be no fuel transport and a power plant would contain heat exchangers, turbines, pumps and condensers all within a single unit. On the other hand, there is an argument that this is highly risky due to large amounts of Uranium and Plutonium close to a tokamak. If the temperature of the superconducting magnets were to rise rapidly, they would lose their superconductivity and plasma confinement would be lost. This ‘quenching’ can damage the walls of the toroid and nearby equipment, even though the fusion reaction would not continue. Therefore, it may not be a good idea to place large amount of radioactive material close to a tokamak [2].

However, with proper design as well as redundant power supplies to the magnets, disruptions can be avoided. A promising compromise might be to still place the fission reactors nearby, but at a safe distance. Although quenching of the superconductors can damage a tokamak wall, there is no risk of a large explosion [2].

The economics of projects such as ITER are a real challenge as the technology must become financially viable at some point in the future. Originally ITER had a planned capital cost of $5 billion, but over the years it kept growing, with the latest figure at around $25 billion. To make matters worse, ITER has experienced several delays from the project start in 2005 as first plasma tests were planned back in 2016. They have been postponed for 2025 and experiments are now planned for 2035. Nevertheless, this is expected with new untested megaprojects and the knowledge gained will help refine the technology. For now, fusion-fission hybrids are a solution to these problems and can provide a valuable stepping stone until pure fusion is realised [2].

Currently, nuclear power is competitive on price with other energy sources apart from where there is direct access to large reserves of fossil fuels, mainly coal and natural gas. There is a large upfront capital cost to build nuclear power plants of any kind and this will likely be the case with fusion plants as well. However, they are much cheaper to run owing to their smaller fuel consumption and long operating lives (most new plants are expected to run for about 60 years) [17].

Interestingly, France and Germany are each focusing on investments in two different energy sources. France relies heavily on nuclear which supplies 80% of its needs, while Germany has opted to phase out nuclear reactors in favour of getting a quarter of its power from photovoltaics and wind. As it stands, France has one of the lowest electricity prices in Europe at around €0.19 per kilowatt-hour whereas in Germany this figure is roughly €0.35. Of course, solar and wind will not always remain expensive as they are improving constantly. Photovoltaics, for example, have seen a dramatic fall in cost in the past decade combined with a rapid rise in their efficiency. While traditional renewables are very important, investing in new nuclear technologies at the same time would help accelerate a transition to lower cost sustainable energy [2].

Can nuclear power become sustainable?

Nuclear fusion is definitely a sustainable process. Deuterium can easily be extracted from sea water while Tritium is replenished using Lithium during fusion. Reserves of Lithium in the crust and oceans combined are predicted to last for millions of years. Fusion energy eliminates the safety and pollution drawbacks faced by conventional fission power plants.

By the end of the century, humanity will likely master nuclear fusion power on a large scale. As technology improves, the huge capital costs will go down until power plants become financially profitable. Eventually, competition between private companies would create innovations that will accelerate this process.

Until the engineering hurdles of pure fusion energy are overcome, breeder reactors offer an excellent solution. They will extend the available supply of fission fuels, namely allowing us to use nearly all the Uranium and Thorium deposits on Earth, of which there are ample reserves as shown in Figure 8. Taking this further, hybrid fusion-fission breeder reactors improve normal breeders’ efficiency by an order of magnitude.

References

[1] H. Ritchie and M. Roser, “Energy”, Our World in Data, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/energy. [Accessed: 18- Feb- 2020].

[2] W. Manheimer, “Mid Century Carbon Free Sustainable Energy Development Based on Fusion Breeding *”, IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 64954-64969, 2018. Available: 10.1109/access.2018.2877672 [Accessed 6 February 2020].

[3] A Dictionary of Physics. Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 360-361, 548-549.

[4] “HyperPhysics”, Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/hframe.html. [Accessed: 12- Feb- 2020].

[5] “What is fusion?”, Iter.org, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.iter.org/sci/whatisfusion. [Accessed: 10- Feb- 2020].

[6] “What is ITER?”, ITER, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.iter.org/proj/inafewlines. [Accessed: 03- Feb- 2020].

[7] “Machine”, ITER, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.iter.org/mach. [Accessed: 08- Feb- 2020].

[8] “Nuclear Fusion”, Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/NucEne/fusion.html. [Accessed: 15- Feb- 2020].

[9] “Nuclear Binding Energy”, Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/NucEne/nucbin.html#c5. [Accessed: 15- Feb- 2020].

[10] M. Kaku, Physics Of The Future. New York: Anchor Books, 2012, pp. 234-246.

[11] “Wendelstein 7-X”, Ipp.mpg.de, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.ipp.mpg.de/w7x. [Accessed: 14- Feb- 2020].

[12] N. Touran, “Thorium As Nuclear Fuel: the good and the bad”, What is nuclear?, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://whatisnuclear.com/thorium.html. [Accessed: 16- Feb- 2020].

[13] “Thorium – World Nuclear Association”, World-nuclear.org, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/thorium.aspx#b. [Accessed: 10- Feb- 2020].

[14] N. Touran, “Molten Salt Reactors”, What is nuclear?, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://whatisnuclear.com/msr.html. [Accessed: 18- Feb- 2020].

[15] “Breeder reactor – Energy Education”, Energyeducation.ca, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Breeder_reactor. [Accessed: 13- Feb- 2020].

[16] “Hybrid Fusion-Fission”, Efn-uk.org, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://www.efn-uk.org/fusion/hybrids/. [Accessed: 09- Feb- 2020].

[17] “Information Library – World Nuclear Association”, World-nuclear.org, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/economic-aspects.aspx. [Accessed: 10- Feb- 2020].